Weather**

What we band in fall has a lot to do with weather in the preceding seasons, even those in years past. I'll leave aside the amazingly wet spring and very hot summer we had in 2011 -- not that they can't have lingering effects, but the weather in 2012 was unusual enough.

We started the growing season well ahead of schedule, with an unprecedented March heat wave. I discussed possible effects in this blog post. Then came the extended hot, dry summer. It began with 11 days over 90 degrees by the end of June resulting in an average temperature for the first six months of the year being the warmest on record for Detroit. Record heat in July (13 more days over 90F) and precipitation well below normal created severe drought conditions (D2 on the U.S. Drought Monitor scale).

Below is a map at roughly the end of the breeding season for many songbirds showing drought conditions throughout North America.

|

| Click here for the original map in detail from the North American Drought Monitor. |

Summary

We ended up banding just 616 new birds and handling 72 recaptures of 63 species (includes two species released unbanded, Ruby-throated Hummingbird and House Sparrow, and one species, Downy Woodpecker, in which we only had a recapture and no new individuals banded). A total of 725 birds were netted (which includes birds released unbanded). Our capture rate was 27.5 birds per 100 net-hours. Here is how this fall compared with the 20 previous autumn seasons:

| Fall 2012 | Previous fall mean |

|

| Days open | 38 | 51 |

| New birds | 616 | 1205 |

| Total birds | 725 | 1541 |

| Capture rate | 27.5 | 49.0 |

| Species | 63 | 70 |

Bold indicates the lowest numbers in our history for fall banding -- we'll give this some analysis in the trends section, below.

The top ten bird species banded this fall (new captures only) were:

- American Robin -- 107 (low; previous mean 188)

- Song Sparrow -- 37

- Blackpoll Warbler -- 36

- Gray Catbird -- 32 (new record low; previous mean 138)

- American Goldfinch -- 32

- Swainson's Thrush -- 30 (low)

- Magnolia Warbler -- 27

- Hermit Thrush and American Redstart -- 26

- White-crowned Sparrow -- 21

Highlights

Let's start out with good news. First, we had our first new species for the banding program in a long while. This handsome male American Kestrel was the first banded on campus by RRBO, and represented the 123rd species banded since 1992.

Connecticut Warblers are always a treat -- especially good-looking adult males like the one below, banded on 19 September.

What started out as a gruesome discovery on 28 September had a happy ending. We captured a Swainson's Thrush that had a piece of straw (hay) impaled through its eyelid and the skin past the ear hole. It was embedded at that point, the skin beginning to grow around it. This must have happened at least several days prior to our catching it, when the bird was foraging in some area with straw strewn about. Amazingly, the eye itself was unharmed, there was no infection, and the bird was in good condition.

|

| Before. |

|

| After. |

|

| "Gambel's" White-crowned Sparrow? |

Trends

The RRBO banding program has focused on bird community composition and various metrics relating to the condition of migrant birds at our site. Thus, overall numbers have not been a main theme for us. Limitations and biases inherent in migration banding cannot be overcome, and much has been published in the literature cautioning against the sole use of banding data to monitor bird population trends. However, it's always interesting to take a look at trends of some species, especially in a year like this with unusual climate events and very low numbers. We just need to take it with a grain of salt.

Of the 25 species of which RRBO has banded over 200 birds, five were banded in greater than average numbers and the rest were below average, when effort was considered*. A half-dozen of these species are among our most commonly banded, and all those were banded in numbers far below normal. Low numbers of a few of them (Hermit Thrush, Song Sparrow, American Goldfinch) could be attributed to the premature ending of the banding season, when I tend to band quite a few of these species. Let's look at the others.

Both Swainson's Thrushes and Gray Catbirds continued a long-term decline in our nets that I wrote about last year. Catbirds in particular I think may be responding to landscape-scale habitat changes being engineered by a burgeoning deer herd.

I'm not sure what to think of the -74% departure from normal of White-throated Sparrows. While they do persist longer in the season here than White-crowned Sparrows (many overwinter), they have been scarce at local feeders as well. This is the first fall season when White-crowns outnumbered White-throats, which are typically banded in three times the numbers. If I had to pick a reason, I would guess that White-throated Sparrows, since they most often feed on the ground, may have had trouble finding leaf-litter invertebrates due to dry conditions. This would be especially true during migration, but it could have impacted them on the nesting grounds as well.

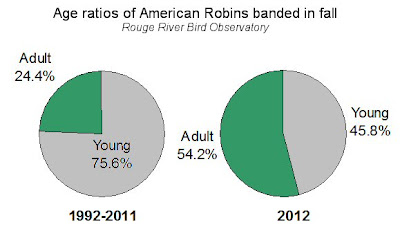

Early in the banding season, I wrote about the lack of young birds being banded. This usually indicates low reproductive productivity. Typically, 81% of the birds we band in fall are young-of-the-year (or hatching-year, HY, birds). This year, just 72% were HY. A look at American Robins, our most commonly-banded species, is instructive.

We've banded nearly 4,000 robins in fall, and roughly three-quarters are HY. This year, the figure was just 46%.

I think this is likely attributable mostly to the drought, as robins rely heavily on leaf litter insects and soil invertebrates (such as worms) to feed their young.

Another interesting metric appeared late in the season. By mid-October, most robins have completed molting -- young birds will have lost their distinctive breast spots and adults will have completed molting their wing feathers. This year that was not the case.

Young robins with breast spots after 10 October:

1992-2011: 2.9%

Fall 2012: 25%

Adult robins still molting primary feathers after 10 October:

1992-2011: 16.1%

Fall 2012: 25%

This indicates that many robins nested later this season. I expect this was due to re-nesting after lost broods (because of the drought), perhaps additionally influenced or initiated by the mid-August rains.

Finally, while I've already provided the caveat that our banding program is not designed to accurately monitor population trends, I have to look at the overall trend in our capture rate for the last eight fall seasons:

Prior to that, there were ups and downs but our effort and capture rate remained fairly stable. We have been banding in the same location all these years, and strive to keep the vegetation structure at its original stage of succession. This may be an indication that populations of the species we typically band in fall are truly declining, and/or that the landscape surrounding our banding area is changing through urbanization, fragmentation, the interactions of deer and canopy loss due to emerald ash borer, or a combination of these and other factors. The value of long-term data collection is having these trends to look at, even if we are not sure how to interpret them at this time.

Recaptures

Twenty-two individuals of 10 species of passage migrants (those which do not normally nest or winter in this area) were recaptured. Seventy-seven percent of them maintained or gained mass.

|

| The old man cardinal. More RRBO longevity records here. |

Six Gray Catbirds from the past were recaptured; there were two from 2008 that were both originally captured as adults. A Downy Woodpecker first banded in 2006 as an adult at least three years old was also back again.

Finally, I’d like to thank this year’s banding crew: Shelley Martinez, Mike Sullivan, and Dana Wloch. RRBO couldn’t operate without you!

*In order to compare different locations or years that may operate the same number of hours but with more or fewer nets, capture rate is calculated by "net-hours." One net hour is one 12-meter net open one hour, or two 6-meter nets open one hour, etc. This rate is often expressed per 100 net-hours for more manageable numbers.

*Weather statistics from the National Weather Service.